The Evolution of Philippine Comfort Food

Whether it’s the aroma of a sour broth wafting through lazy afternoons, or the sight of a hearty adobo simmering on a kalan, every Filipino carries memories of their childhood comfort food. These memories might seem eternal and unchanging, but the recipes in them have always defied stagnancy — they evolve with every generation, adapting to new tastes, ingredients, and ways of life. How we prepare our comfort food can say a lot about our culture, serving as a living expression of what it means to be Filipino and the reinvention that comes with that. But how exactly did the adobo and sinigang that we know and love come about?

Long before the Spaniards arrived on our shores, Filipinos were already using vinegar (from sources like coconut, nipa, sugarcane, etc.) combined with salt to preserve meat, fish, and other game against spoilage — a constant battle against the tropical climate of the archipelago. The term “kilawin” also emerged from this time, not as the recipe we know, but as another method of preservation — marination and soaking in vinegar.

When the Spaniards arrived, they were intrigued by how locals preserved their food — simmering meat in vinegar and salt to keep it fresh in the tropical heat. They called the method “adobo de los naturales,” or “adobo of the natives.” The term adobo itself comes from the Spanish word adobar, meaning “to marinate” or “to pickle.” Funnily enough, the dish we now call adobo wasn’t derived from a recipe, but from methods of preservation that utilized what the islands had.

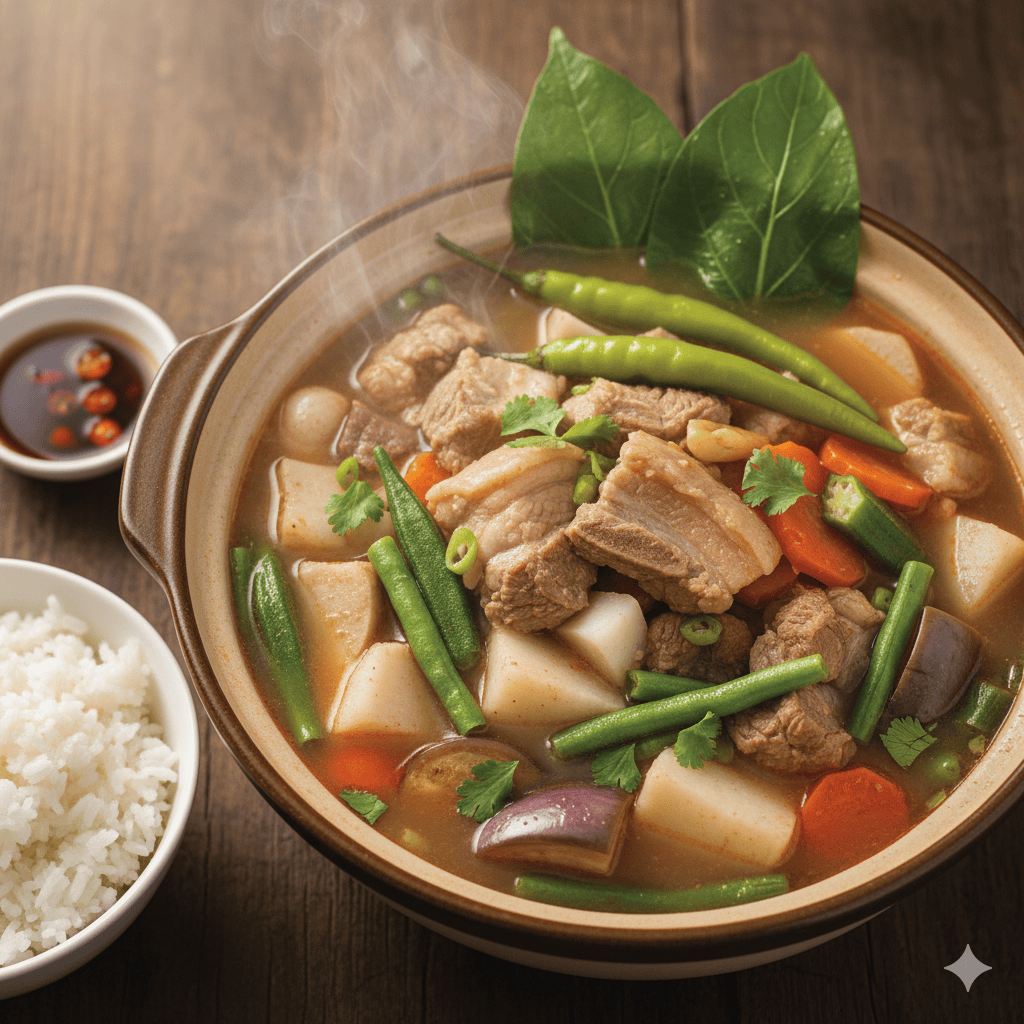

Sinigang has a similarly fascinating history. While today it’s mostly associated with sampalok (tamarind), early Filipino natives relied on whatever sour fruits or plants were available nearby: kamias, bayabas (guava), santol, calamansi, or unripe mangoes. Long before recipes circulated on TikTok or food blogs, sinigang was a taste of the land itself. These pre-colonial recipes might have been practical and local, but they evolved into cultural cornerstones — symbols of how resourcefulness can be turned into flavor.

Adobo didn’t stop there though, while Spanish colonizers named it after their own vinegar-based dish, the Filipino method was undoubtedly older, yet strangely more open to change. When Chinese traders came, they brought with them the magic of soy sauce — introducing one of the key ingredients almost every Filipino adobo dish in the modern era uses in abundance. Sinigang transformed too, absorbing influences like imported meats or bouillon from travellers and cultural exchanges. That being said, through the centuries, both dishes remained deeply Filipino — flexible, inclusive, and tied to memory.

Even regionally, the evolution and existence of these comfort foods vary. From adobong dilaw with turmeric in Batangas to adobong manok sa gata in Bicol, part of the magic of the Filipino cuisine is the diversity and radical changes you come across just by skipping over a few islands. Sinigang itself can change drastically, depending on whether it’s soured with sampalok, batuan (an endemic Philippine fruit), kamias, or even strawberries in the North. Yet, throughout all of these variations, the dishes are unified by one trait: a sense of comfort and home.

Nowadays though, the question becomes what comfort food looks like in the modern kitchen? Urbanity and development have undoubtedly changed how Filipinos cook — there’s less time, smaller kitchens, yet the same passion and craving for warmth and flavor. This is where ready-to-use sauces and kitchen aids come in.

Products like the TasteSetters® Brand sauces and pastes make it not just possible, but easy to make our comfort foods. Whether it’s whipping up a nostalgic adobo with our Soy-Based Sauce or Beef Flavor Savory Paste in your hearty sinigang, TasteSetters® Brand has committed itself to helping chefs and home cooks explore new flavors while keeping true to Filipino roots — showcasing how innovation and tradition can share one plate. Globally, dishes like adobo and sinigang have been transformed into extravagant concoctions — adobo plated gourmet-style, sinigang served as a consommé, while still somehow keeping that taste of home. The advent of fusion cooking has introduced even more evolutions to the meals we know and love, telling stories of migration, creativity, and continuity.

Adobo and sinigang are living traditions — every simmered pot and sour sip tells a story of who we are and how we’ve changed. Whether preserved by memory or reimagined with modern tools, the Filipino spirit endures. After all, the essence of comfort food is not something rooted in the past. It evolves, as it should. Just like the people who make it.